The Witches of Essex community heritage project was a six-month project bringing members of the local community together to learn about the local stories of the Essex witchcraft trials. We worked with the Essex Records Office and Professor Marion Gibson to learn how to research as Historians, access and use artefacts and archives before devising a short theatrical performance and free education resource to share with the community. We learnt about who the accused were and why they were accused? We researched about the Trials , investigations and punishments and the impact which their stories have had upon us today. The project was supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund.

And the Project starts…

Engaging with the Community:

Right from the outset it was important for us to capture the attention of local people and encourage them to get involved and learn about the past. In preparation for the project, we used several tried and tested strategies as part of our public engagement strategy. These included:

-Posters and leaflets

-Social media (Our Instagram, Twitter and Facebook pages

-Library displays

-Invites to past members of our heritage projects

-Meet and greet sessions at local community groups

-Posters displayed at local Universities and LSE Library

-Word of mouth

And many more…

We were blown away by the number of people wanting to take part. We saw our BIGGEST intake of participants so far for our heritage projects

Working with the Essex Records Office

Our visit to the Essex Records Office was a huge success and incredibly helpful towards our research. From the outset, Vicky made us all feel welcome and supported. She showed us around the archives before giving us a really insightful introduction to what life was like living in Essex during the 15th and 16th centuries. It helped to set the scene and visualise what living conditions were like. It opened our eyes up to some of the reasons why people were being accused of witchcraft.

Vicky then helped us to explore the language at the time and the way that things were written down. We played detectives translating diaries, records and understanding them. This was a really fantastic learning opportunity for us as it allowed us to start thinking historically. Some of the details we learnt were invaluable.

Kate then showed us around the Sound Archives, talking to us about the history and how sound archives have evolved. We looked at different pieces of equipment before looking into the different things to be aware of when creating audio files. One of these was the use of dialect. Who would have thought there would be so many Essex accents! She gave us tips for creating our sound files which was really useful.

Read our Blog about our visit to the Essex Records Office here

Setting the scene

Medieval folk had long suspected that the Devil was carrying out his work on earth with the help of his minions. England – and Essex in particular – was in the grip of witch fever. Between 1560 and 1680, 317 women and 23 men were tried for witchcraft in Essex alone, and over 100 were hanged.

Witchcraft as a crime

Practising witchcraft was not a capital offence to begin with. However, in 1484 Pope Innocent III declared witchcraft as heresy, and this was a capital offence. Despite this capital punishments for witchcraft were extremely rare.

In 1542, under Henry VIII, a bill called “The Bill Against Conjurations & Witchcrafts and Sorcery and Enchantments” was created. This meant that for the first time in English history, witchcraft was now a crime to be tried in normal courts - the same ones used for all other crimes such as murder and theft. It was punishable by death and forfeiting of property, land and possessions.

The Witchcraft Act

In 1563, during the reign of Elizabeth I, The Witchcraft Act (1563) was passed: “An Act Against Conjurations, Enchantments and Witchcrafts”. The Act stated that, in cases where witchcraft resulted in death, it is punishable by death. However, in lesser cases (i.e. not resulting in death), it is punishable by a term of imprisonment.

After the 1563 Act convictions for homicide caused by witchcraft began appearing. Out of 1158 homicide victims 228 were suspected to be caused by witchcraft. 157 people were accused of killing with witchcraft, of which around half were acquitted. Only nine of the accused were men.

Setting the scene in Essex

Witches appeared to be more prevalent in the Eastern counties, particularly in isolated communities. Most were individuals, though some larger groups were found in Maldon, Hadleigh, and Coggeshall, although they were not organised enough to have been covens. Between 1560 and 1675, over 650 Essex men and women were accused of being or consorting with witches. Some were hanged, others died whilst awaiting trial, but many were found not guilty. Granted, the experience wasn’t going to be pleasant, life after acquittal was probably also going to be rough, and the chances of you being accused again were high, but many of the accused were acquitted.

For the people of Essex, times were very tough. Poverty was high and living standards were very poor. Disease and illnesses were common. People couldn’t afford doctors back then so they would go to local people with knowledge of herbal and spiritual remedies. Living in the villagers such as St Osyth, Coggeshall, Clacton and Manningtree were particularly hard where folk depended upon working the land and were dependent upon their crops or livestock. Many villages ran a barter system which often created arguments between neighbours. Law and order were upheld by the local landowners of power (Who were often local Magistrates) such as Brian Darcy and local clergymen.

The word of witchcraft spread fast, and people quickly began blaming bad crops, disease and bad times upon witchcraft. People became paranoid and were influenced by stories and started accusing their neighbours, friends and even family members.

You can download our article “Setting the scene: The history of the Essex Witchcraft Trials” here

Alternatively, you can listen to the article here:

Who was accused of witchcraft?

Common Traits of a Witch

Typically, those accused of witchcraft were predominantly women, often marginalized individuals such as the poor, elderly, or those who did not conform to societal norms.

In Europe as a whole, more than 70% of those accused of witchcraft were women. In Essex, between 1560 and 1680, 317 women and 23 men were tried for witchcraft and over 100 were hanged. To begin with our research began pointing towards the following common traits of those accused:

1.Most were women

The facts and numbers do indeed speak for themselves. Most of those accused were women. They were often labelled as ‘witches’ due to their non-conforming attitudes. Often those accused had lived hard lives and had born illegitimate children which was seen as a sin in the eyes of the church. The wives or families of those whose husbands strayed the field would happily see the other parties accused of witchcraft as an act of revenge.

2.Vulnerability and disability

We found that in many of the stories about those accused, they were vulnerable people. They lived either alone, elderly or in poverty or were one-parent families. They often did not have the knowledge or the money to seek legal defence. Some did not have the confidence to fight back. We also found that there were several cases such as that of Elizabeth Clarke and Dummy who had disabilities and this was seen as a weakness and an ideal opportunity to take advantage of them by fooling them into making confessions for things they had not done wrong.

3.Social outcasts

Those who were marginalized or lived on the outskirts of society. People like Ursley Kemp who were believed to have lived ‘colourful lives’ against the norm of the church. It could even be as simple as that they lacked confidence in social situations, were homeless, poor, elderly or just lonely. Professor Marion Gibson highlighted that the fear of witchcraft often intensified during times of social upheaval such as wars, famine or disease. People were often looking for someone else to blame. Joan Prentice was hanged because she had a pet ferret!

4. Ordinary people

Some people were just ordinary folk trying to mind their own business. Many accusations stemmed from family feuds or arguments between neighbours. We found this to be a common factor in many of the stories read. Both Cisley and Henry and Anges Waterhouse were prime examples. These arguments could be about livestock, money owed or even as daft as feuds over who borrowed a jug of milk to who. This reflected how the local dynamics could lead to witchcraft accusations.

However, the further we researched, we did find that there was a general misconception amongst common belief that all women accused were from poor backgrounds. In fact, 64% of those accused in Scotland alone were from middle class backgrounds. This was mirrored across Europe.

What is clear, is that those in power believed that women were weaker and more easily tempted than men. In the bible story of Adam and Eve, it is Eve who is tempted by Satan to eat the forbidden apple. Woman are considered more of a risk of being influenced by the Devil.

You can download our article “Who was accused of Witchcraft?” here

Alternatively, you can listen to the article here:

VISUAL LEARNER?

You can watch it here instead if you prefer!

Why were people accused of witchcraft? – The motives

There are many reasons as to why people were accused of witchcraft. Some were due to personal reasons including arguments amongst neighbours, fear or even acts of revenge. While other reasons were more generalised across the whole country and Europe. In our research, we set out to identify some of these motives.

The Monarchy and the church

Medieval folk had long suspected that the Devil was carrying out his work on earth with the help of his minions. England – and Essex in particular – was in the grip of witch fever. We know that there had also been a heavy influence from other countries across Europe and the world. Both the monarchy and the church were strong believers in the fight against what they perceived as evil. It also posed as a great way of manipulating others, spreading fear and then gaining control and power. Laws such as the Witchcraft Act were passed, King James even wrote the Daemonologie book about witchcraft and clergymen would regularly give sermons.

Literature and word of mouth

One of the biggest contributors to the increase in persecutions of suspected witches was the development of mass printing. This technology allowed new ideas to be spread far and wide, with those able to read being exposed to a whole new world of ideas. It also created stories and rumours which were then spread from word of mouth throughout towns and villages.

Looking for someone to blame

Much of the local villages depended upon working the land. Poverty and disease were ripe amongst the villages and towns. Sanitary conditions were poor. Money was scarce and barter systems were part

of everyday life.

Disagreements often erupted

among neighbours, and law

and order was upheld by local

estate owners such as Brian

D'Arcy, the clergymen and

magistrates. One way of getting

back at your neighbours was to start vicious rumours about them being a witch or even put in a complaint to the local Clergyman or Magistrate.

Morale was often low particularly when disease outbreaks and poor harvests caused further hardship. Often wiping out families. People were often looking for something or someone to blame. Professor Marion Gibson highlighted this area in her book “The Witches of St Osyth” when writing about the story of Cisley and Henry. Many thought that disease and bad luck was caused by the devil himself or by wrongdoing. Who better to blame than someone who appeared to be in touch with spirits.

Manipulation and self-gain

Another common reason as to why someone would accuse another person of witchcraft was because they were looking to gain something for themselves. This could be social status within the community, power or financial / land ownership gain. Indeed, it is strongly argued that both Brian Darcy and Matthew Hopkins motives were simply to climb the social status and financial wealth.

You can download our article “Who was accused of Witchcraft?” here

Alternatively, you can listen to the article here:

VISUAL LEARNER?

You can watch it here instead if you prefer!

Focused character workshop:

What were people’s views of witchcraft in the 1500-1600s Essex and how did it feel to be accused?

As part of our research application work, we used our research from the Essex Records Office and Professor Marion Gibson to explore the attitudes towards witchcraft in Essex during the 1500-1600s particularly in rural communities. This helped is to set the scene as a starting point in our research. We knew that there were many external factors which affected people’s views and making them far more suspicious and easily persuaded in their conclusions. These included:

-Economic hardship

-Disease and death rate

-Problems in farming and land

-Religious influence

-Expanding literature and reporting. (Media and scaremongering)

We also used from our visits to the Essex Records office where they gave us an introduction to what life was like living locally during this time period and living conditions were especially for the working-class families in rural areas of Essex.

During our workshop we used group work, discussions and performance techniques to explore societies attitudes towards witchcraft in the community at the time. We quickly realised that these attitudes were heavily influenced by external beliefs and opinions. We set out to answer the following key questions:

1.What were societies views towards witchcraft at the time?

2. Why were people accusing their neighbours of witchcraft?

3. How did it feel to be accused of witchcraft?

4.What were the possible motives behind the investigators and how did this affect the outcomes of the accusations?

.jpg)

Common words which came up to why people were accusing others included:

-Fear

-Frustration

-Anger at their hardships

-Lack of understanding / misinformation

-Revenge / breakdown of relationships

We found that there were common traits in those being accused of witchcraft. Many were poor, had children out of wedlock, had disabilities, were spiritual or creative women. We compared this to how society is today and asked the question of whether we have made any progress or whether we are still prejudice towards people who are different or vulnerable in the community.

People were accused of witchcraft were made to feel more vulnerable, afraid, defensive, isolated, paranoid, desperate, angry and judged. They were investigated unfairly and often tortured until they gave in to believing what their investigators wanted. It was clearly an unfair and unjust society. It some ways, it still mirrors parts of our own society today. It gave us an insight into how it felt to be one of those people accused which helped us to gain a stronger sense of empathy whilst re-creating their stories for our learning resources.

Above: Examples of our mind mapping

You can download a copy of our article/ blog written about our focused character workshop here:

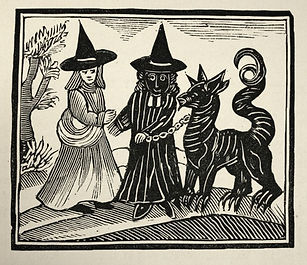

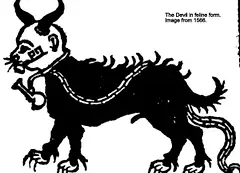

Witches and their imps and familiars

Familiars are mystical companions often associated with witches, serving as guides, protectors, and assistants in magical practices, with a rich history that spans folklore and modern witchcraft.

In 1604, James I introduced a new Witchcraft Act that included “the occult rituals of diabolic witchcraft” (Voltmer 2017: 110). This made working with evil spirits a capital offence. The act also referenced familiars, believed to be “the witches’ helpful demonic companions” (Voltmer 2017: 110). The Act really made an effort to clarify types of witchcraft. It also turned communicating with spirits and practicing magic with body parts into capital offences (Voltmer 2017: 110).

By the time we reach the witch hunts of the 17th century, these familiars were more “popularly referred to as ‘imps'” They manifested as small animals and a witch’s power could pass to another person through the familiar.

Familiars in our Essex Witchcraft stories

They were mentioned as key pieces of evidence against many of those accused in the Essex witchcraft

trials. Joan Prentices was

said to have a

ferret named Satan

or Bid while Cisley

of Clacton was

reported to have

familiars who would

feed upon her blood.

In many of the stories,

those accused were said to have used their familiars to cast nasty spells upon their victims often resulting in death. Many of the accounts came from this area thanks to the activities of Matthew Hopkins, the self-proclaimed witchfinder general. In East Anglian folklore, witches either got their familiar direct from Satan, or they inherited them from someone else. Surprisingly, these imps still appear in court records in the area as late as the early twentieth century.

People believed familiars were evil spirits.

They fed on the blood of

‘their’ witch and acted as

servants. Many think the

word comes from famulus,

a Latin word for servant.

The famed ‘witch’s mark’,

sought during

investigations, was believed

to be the teat where the

witch suckled her familiar.

Familiars also taught witches how to do magic and dispensed advice. Witches used them as spies thanks to their shapeshifting abilities. Cats, dogs, owls, toads, and mice all fell under suspicion.

Looking for a list of all the common familiars?

We’ve attached a table of all the names of the common familiars in our article.

You can download a copy of our article all about The Witches Familiars and their imps by clicking the button below:

Trials and punishments

The witch trials

The typical victim of an English witch trial was a poor old woman with a bad reputation, who was accused by her neighbours of having a familiar and of having injured or caused harm to other people's livestock by use of sorcery.

About 500 people are estimated to have been executed for witchcraft in England. It didn't take too much to be accused of witchcraft. In difficult times, such as years when crops failed or disease was widespread, communities would often look for supernatural causes. Witches were seen as one such supernatural cause.

Anyone who had become ill or suffered a sudden misfortune might look for a magical reason among the people around them. Accusations of witchcraft usually came from within the suspect's community. Often, they involved a dispute or argument, after which one of the people involved suffered some ill health or misfortune

When someone was accused of witchcraft, they were often investigated by someone seen as having authority within the community. In St Osyth this was often the local Magistrate Brian Darcy. Evidence and interviews with local neighbours, clergymen were undertaken. Those accused would be summoned to see the Magistrate for questioning. They would be sent for and marched through the streets in plain view of everyone to see. They would be strip searched by associates such as Margaret Simpson who would search their bodies for markings, scars, body features which were not deemed to be normal. Specimens were taken and it was not a very comfortable procedure. People who were of the poor and vulnerable were often picked on as they lacked the power or ability to defend themselves. Another common attribute was women who had born children out of wedlock which was seen as a sin in the eyes of the local clergymen.

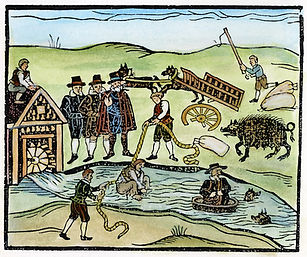

Torture:

Although torture was not supposed to happen, it often did. Those accused were often submitted to often degrading, painful and dangerous forms of torture. Darcy would often put those accused in a dark room for hours without food, drink or any knowledge of what will happen and observe their behaviour. He would also keep the accused awake for long periods of time – often many days. This technique was called “Waking the witch.” Matthew Hopkins often used forms of torture to ‘test’ to see whether people were witches. The Swimming test was one example where a woman is tied and lowered into water. If she floats, then she will be deemed to be a witch. If sinks (and often drowns) she is seen to be innocent.

The Devil’s mark was another test. It was thought that when a witch pledged herself to the Devil, he marked them with a sign of their loyalty. This Devil’s Mark was an area on a witch's bodies that would not respond to pain. Witchcraft investigators used sharp tools to prick the skin of suspected witches to see if the Devil’s Mark could be found. Some people worked as professional witch prickers.

This was painful and highly distressing, and, although not originally intended as a form of torture, it may have been used as torture to bring about a confession. Even finding a birth mark or a mole on the skin could be enough to accuse a person of being a witch.

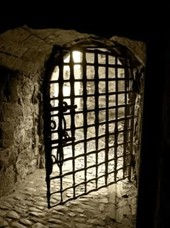

Another example is Ursula Kemp from St Osyth who went through many accusations and ended up being hanged. She was known to reside in "the cage" during her trial. In medieval times, "the cage" which is a type of prison, was often a form of public humiliation and confinement used to punish criminals. The structure was typically a small, barred enclosure, sometimes suspended in public places like market squares or outside castles, where individuals were left exposed to the elements. It was not only a form of physical restraint but also served to publicly shame the prisoner, reinforcing the societal power dynamics of punishment and authority.

Assizes:

The Assizes ‘trials’ were held in quarterly sessions throughout the year. Judges from London would travel to lead these court proceedings. The streets would often be filled with people who had come out to see the trials take place. People would be selling souvenirs, food and drink. Witchcraft was a crime that came to Assize courts regularly, but only after a new Witchcraft Act had been passed by Parliament in 1563. The new Act stated that witches who were convicted of lesser offences – like making farm animals sick – would be punished with one year in prison. Witches who were convicted of killing a person, however, were to be hanged.

Those accused would be brought through the streets wearing shackles and ragged clothes. They would be dirty from my time in the prison cell awaiting trial. They would e traumatised and frightened. They would be mocked, faced with insults and have things such as rotten food thrown at them by passers-by.

The trial itself would be in front of a judge, magistrates and jury. The evidence would be heard and, in some cases, those accused would come face to face with the people who had accused them. Often, they would have confessed beforehand to the crime.

Many of those accused were executed. This was most commonly done by strangling the alleged witch and then burning their body.

Destroying a witches body made sure that it could not be brought back to life by the devil or be used for evil magic. It also meant those found guilty of witchcraft could not receive a Christian burial.

“The Chelmsford Assizes was an open-sided building, with eight oak columns supporting upper galleries and a tiled roof. The galleries, which overlooked the open “piazza” below, were lit by three dormer windows in the roof… the magistrates and justices sat in open court, which measured only 26 feet by 24 feet, with the officers of the law, counsel and clerks, plaintiffs and defendants, jurors, sureties, witnesses and prisoners, before and around them, while spectators, hangers-on, and those awaiting their turn, crowded into the galleries above or thronged the street outside.”

VISUAL LEARNER?

You can watch it here instead if you prefer!

You can download a copy of our article/ blog written about our focused character workshop here:

Alternatively, you can listen to the article here:

The trial of Agnes Waterhouse – A drama enactment

Whilst learning about the investigations, trials and punishments of those accused of witchcraft, we came across the story of Agnes Waterhouse. Agnes from Hatfield Peverel was accused and then put on trial for witchcraft. She was investigated by Matthew Hopkins. We used our research to create an enactment bringing to life her trial so that it helped us to build a better understanding of how those accused were treated.

You can download a copy of our devised play here:

Alternatively, you can listen to the article here:

VISUAL LEARNER?

You can watch it here instead if you prefer!

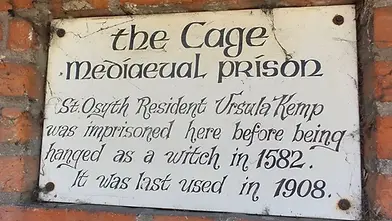

The Cage

The history behind the famous lock up in St Osyth

The Cage is a former village lockup where drunks and villains would be kept overnight. It is claimed that Ursula Kempe was detained here in 1582 whilst being interrogated over false accusations of witchcraft. We know of no evidence to support this, but she certainly was interrogated at St Clere's Hall. Ursula was hanged in Chelmsford together with another St Osyth woman Elizabeth Bennett.

The history of the Cage

St Osyth, a charming village nestled on the Essex coast, whispers tales of a past far richer and, at times, far darker than its idyllic present suggests. Among its historical treasures, one structure stands out, a stark reminder of a bygone era of injustice, fear and oppression: The Cage. More than just a building, The Cage is believed to have ties to St Osyth’s dark history, particularly its infamous witch trials and the role it would play as the town’s lock-up. The building has also built a reputation amongst paranormal investigators, with many claiming it to be one of the UK’s most haunted houses.

The Town Lockup (c. 1500 – 1908)

The story of The Cage, in its earliest iterations, likely began as a functional necessity for the small village. Before it earned its chilling reputation, this rudimentary structure was believed to have served as the town lock-up – a place where minor offenders, vagrants, or those awaiting transport to larger courts would be held. It was a means of ensuring order within the community, a visible deterrent, and a temporary holding space for those who disrupted the peace or broke the law. The structure itself would have been a cold place of isolation, where many undoubtedly spent times reflecting on their past indiscretions.

In the 19th century, legislation was introduced placing pressure on local councils to establish more orderly police forces leading to many Cages across England becoming disused or repurposed, though many were still in use after this time, particularly in small, regional towns like St Osyth. A plaque added to The Cage during its reconstruction in the 20th century suggests that The Cage may have been used as late as 1908, now serving as an important record of the building’s former use. To this day, the role of The Cage serving as the town lockup continues to be upheld by local historians, the St Osyth Historic Society and the St Osyth Museum.

One of the Cage's most famous guests was of course, Ursley Kemp who was accused of witchcraft. It is believed that she was held here awaiting her trial.

You can download our complete article "The Cage" here:

Alternatively, you can listen to the article here:

Colchester Castle Prison

Colchester Castle was a key landmark in the Essex witch trials. In the 1500s and 1600s, hundreds of people were imprisoned inside its walls suspected of being a witch

The county became well known for its persecution of suspected witches, the first person in England to be executed under a Witchcraft Act was Elizabeth Lowys who lived in Great Waltham. Five hundred years later, many of the stories of victims like Elizabeth are at risk of being lost – overshadowed by tales of people like the famous Witchfinder General, Matthew Hopkins.

The Castle’s relationship with the Witchcraft Trials

Colchester Castle was the first of the great keeps and the largest built by the Normans in Europe. But by 1645, it had fallen into such a state of disrepair that it was only fit for one purpose: a prison.

Conditions in the gaol were dire.

Accused witches were thrown into prison while awaiting trial, and this was nothing like our modern-day idea of prison. The accused could be held for days, weeks, months and even years in some cases waiting for a trial date. Conditions were unsanitary and the prison cell was the perfect environment for disease to spread. Colchester Castle was first used as a prison in 1226, was the county prison until 1667 and was used until 1835. Many of Hopkins’ victims were held here and the Castle gives us a good idea of how accused witches were treated.

Part of the roof had collapsed a decade prior and exposed prisoners to the elements. Male and female prisoners were separated into two cells and kept shackled. They slept on straw or bare stone. Food was poor and basic cleanliness impossible. Many prisoners, including some of the women accused as witches, died of exposure, malnutrition, or disease.

You can download our article "The Colchester Castle Prison" here:

Alternatively, you can listen to the article here:

Our journey then took us on to researching into two examples of prisons where those accused were kept. This brought us to the famous Cage lockup at St Osyth and of course, the Colchester Castle prison.

Using performance to explore what it was like inside the prisons for those accused

Using role-play we devised two short monologue pieces. The first was based on Ursley Kemp and her time spent in the Cage. The second was of Alice Prestmary who was held at the Colchester Castle prison. Sadly, Alice died whilst in the prison. It was believed that she had become ill and died from her symptoms. You can listen to both of these monologues below:

The Investigators

Brian Darcy: Magistrate, Sheriff and Witchfinder in Essex

Darcy was a magistrate, Sheriff of Essex, witch-hunter and contributor to the 1582 “A true and just recorde of the information, examination and confession of all the witches, taken at S Oses [St Osyth]”. “This argued for harsher punishments for those found guilty of witchcraft, and Darcy was personally responsible for a number of deaths of people accused of witchcraft.

Witch hunts in Essex

The first witch hunt in Essex took place in St Osyth and was led by the D’Arcy family. The first person to be interrogated was the local midwife – Ursula Kemp. She immediately confessed to being a witch and confessed that she had caused the death of a baby.

This started a snowball effect with many women throughout St Osyth and nearby Great Clacton implicated in the alleged witchcraft activities. These activities had apparently taken place in the village and surrounding area.

By the end of Brian D’Arcy’s 1582 witch-hunt, at least 10 women – all from the village or the nearby area – were tried and executed in Chelmsford for murder by witchcraft. Many more were incarcerated in Colchester Castle (Essex’s county gaol) but released after being found not guilty during their trial.

It has been calculated that for the whole of the 1580s, the activities of Brian D’Arcy account for 13% of all trials for all crimes that took place in Essex that decade. That is a tremendously high number! St Osyth today is small. Back then, the population was tiny. Probably every single family or house in the village were under the shadow of this appalling witch-hunt.

After the witch trials were over, Brian D’Arcy got his wish to be all powerful. He became the Sheriff of Essex in 1585. On the back of his witch-hunting activities.

Many people have heard about Matthew Hopkins – the self-styled Witch-finder General. But few know about Brian D’Arcy. Essex’s (and England’s) first witchfinder. Who, for his own political ambitions, conducted England’s first ever witch-hunt – with devastating consequences for local St Osyth’s women.

Brian D’Arcy’s tactics in his investigations

In our research, we found that it could be argued that some of his tactics were found to be rather suspicious to say the least. Records of the investigation including interviews with those accused were tampered with where dates and times changed, questions and responses omitted and information missing. Although, it could be argued that these records have simply been lost over time. One of Brian’s personal tactics was that he would often question the children of those accused before questioning the accused. He would often mislead the children using traps to fool them into giving information and twist the meaning of their responses. The children would then be used against the parents. This was apparent in both the story of Ursley Kemp and then Cisley and Henry. In the later case, he deliberately played on heated and emotional moments within the family’s personal life for personal gain. Professor Marion Gibson highlighted that D’Arcy was particularly proud of his use of trick questions and his false promises of favourable treatment for those who confessed.

Margaret Simpson

During his investigation, D’Arcy would often call upon Margaret Simpson who so happened to be the wife of a local clergyman. (Who often did a lot of the accusing himself) Margaret’s role would be to strip search the accused looking for marks or imperfections which would indicate witchcraft. She would take specimens and notes, and the procedure was extremely traumatic for the accused. Her evidence was often used in trials.

D'Arcy’s investigations were used in detail in the publication of the pamphlet “A true and just recorde of the information, examination and confession of all the witches, taken at S Oses [St Osyth]” which was indeed written by an anonymous author “WW”. Interestingly, it was dedicated to Brian reading “To the right honourable and his singular good lord, he, lord D’Arcy WW wishes a prosperous continuous in their life to the glory of God and a daily preservation in gods fear to his endless joy.” Brian used this publication in his argument for there to be tougher and harsher punishments for those accused of witches. He believed them to be devil worshippers and wanted the punishment of hanging to be changed to burning.

Across today’s Maldon District, the legacy of the D’Arcy family is tremendous. The beautiful village bearing the family’s name. Maldon’s fabulous Moot Hall.

But less known is the legacy of Brian D’Arcy’s terrible witch-hunt of 1582.

Matthew Hopkins

The self-proclaimed Witchfinder General

Self-styled Witchfinder

General, Matthew Hopkins,

and his associates were

responsible for 20% of all

witchcraft executions from

the 15th to 18th centuries,

despite only being in

business for three years.

He was active from 1644 to

1647 and used questionable

methods to investigate

suspected witches.

Records of Hopkins’ early

career in the art of witch

hunting are a tad vague,

however it appears to stem

from when he moved to

Manningtree, Essex in 1644.

An impoverished lawyer with

a strong puritanical

background, Hopkins appears to have seen it as his mission to destroy anything to do with the “works of the devil”.

Hopkins appears to have assumed the title of Witch-Finder General in 1645, claiming to be officially commissioned by Parliament with the brief to uncover and prosecute witches. Together with his entourage that included a merry band of ‘lady prickers’, they travelled the villages and towns of eastern England, trying and examining women for witchcraft.

Payment

Of course, all of this came at a very ‘reasonable’ price, said to be “twenty shillings a town”, although the records reveal that the small market town of Stowmarket paid £23 for his services. A true entrepreneur, Hopkins appears to have quickly turned his mission into a well-paid career, so much so that local taxes were even being levied in order to fund his obsession.

Hopkins methods for investigating those accused were pretty questionable to say the least. They included keeping the suspect awake for days on end, resulting in the suspect, now suffering from sleep deprivation, being coerced into confessing to almost anything. Another method was cutting the arm of the accused with a knife, needle or pin, and if she did not bleed, she was said to be a witch.

The Swimming test

Hopkins methods for investigating those accused were pretty questionable to say the least. They included keeping the suspect awake for days on end, resulting in the suspect, now suffering from sleep deprivation, being coerced into confessing to almost anything. Another method was cutting the arm of the accused with a knife, needle or pin, and if she did not bleed, she was said to be a witch.

Matthew Hopkins and his team usually followed the same steps of prosecution in each case. First, they would use local rumour or suspicion to condemn a witch. Hopkins also claimed to have a “Devils List”, naming all English witches in code. Once condemned the person was tortured until they confessed, usually implicating several others as part of the confession. His reputation, together with the biased view of the majority that the accused was guilty, resulted in a very high conviction rate.

Hopkins’ favourite confessional method of torture however was the infamous “swimming test”. This unbelievably simple but effective test involved binding the arms and legs of the accused to a chair before throwing them into the village pond. If they sank and drowned, they would be innocent and received into heaven; if they floated, they would be tried as a witch.

Between the years 1644 and 1646, Hopkins and his associates are believed to have been responsible for the deaths of 300 women. And in the days when an average farm worker’s wage was just 6 pence a day, it is estimated that Hopkins may have collected fees of around £1000 for his gruesome services.

Death

Hopkins even wrote a short pamphlet detailing his witch-hunting methods: ‘The Discovery of Witches’, which was published in 1647. His own end, however, is far from clear; some accounts say he drowned undergoing his own “swimming trial” after being accused of witchcraft himself.

You can download our article "Matthew Hopkins Witchfinder General" here:

Alternatively, you can listen to the article here:

You can download our article "Brian D'Arcy: Local Magistrate and Witchfinder" here:

Alternatively, you can listen to the article here:

VISUAL LEARNER?

You can watch it here instead if you prefer!

Using performance to explore the roles and motives behind the investigators

Using role-play we devised two short monologue pieces. The first was based on Margaret Simpson who worked alongside Brian D'Arcy/ Her role was to strip search those accused looking for evidence which could imply witchcraft. The second piece is called "My name" based on Matthew Hopkins the witchfinder general. You can listen to both of these monologues below:

Retelling stories of those accused

One of the core aims of our project was to create sound archives to not only preserve local stories of the past, but to create a platform for underrepresented and/or vulnerable voices to be heard. This took our research back to Professor Marion Gibson’s book “The Witches of St Osyth”, the Essex Records Office archives and online research. We found that there to be hundreds of names of people accused of witchcraft. Sadly, we couldn’t tell all of their stories. However, we chose a selection of those voices and using short plays, stories and monologues; we brought these stories to life. Here are a few examples:

Ursley Kempe of St Osyth was an English cunning woman and midwife who in 1582 was tried for witchcraft and hanged. Kemp was accused of (and apparently confessed to) using familiars to kill and bring sickness to her neighbour. She was the first person to be investigated by local Magistrate Brian Darcy. She was reportedly imprisoned in the famous ‘cage’ prison in St Osyth before her trial.

Cisley and Henry from Clacton tells the story of husband and wife Cisley and Henry who were accused of witchcraft by their neighbours. Investigated by Brian D’Arcy, he used his usual tactics of trick questioning and using their children against them. He quickly took advantage of their difficult and emotional family dynamics to secure a confession. Although oddly, it was only Cisley who was convicted and not her husband.

Joan Prentice or Joan Prentis from Sible Hedingham was executed after being accused of witchcraft with Joan Cunny and Joan Upney in Chelmsford in Essex in 1589. It’s said that she was accused after a neighbour had overheard her talking to her pet ferret. When asked, she told investigators about her pet who she said was a ferret named "Satan" or "Bid". The ferret was said to have fed by biting and sucking her blood from her left cheek.

Elizabeth Clarke or Bedinfield of Manningtree was the first woman accused by the Witchfinder General, Matthew Hopkins, in 1645, marking the beginning of a series of witch trials in by him in Essex, England. It was reported that Elizabeth only had one leg. She was accused by local tailor John Rivet. Hopkins and John Stearne took on the role of investigators, stating that they had seen familiars while watching her. During the process, she was deprived of sleep for multiple nights before confessing and implicating other women in the local area. She was tried at Chelmsford assizes, before being hanged for witchcraft.

Annis from Little Oakley was another victim of idle gossip purely because she did not fit in with her local community. Paranoid by the stories of witchcraft spread, they sought out and hounded Annis until she was investigated by the local clergyman and then by local magistrate Brian D’Arcy. Annis from Little Oakley was one of Brian D’Arcy’s later cases of witchcraft. Tet, it still highlights the nature of fear and manipulation from those in higher status within the local community.

Two separate films about Dummy or the man with no name from different perspectives. This is an incredibly sad story of a elderly disabled man who was the final recorded stories of witchcraft recorded in the mid 16th century. It was said that he was deaf and could not speak and only communicated by sounds. He lived on the outskirts of Sible Hedingham tendering to his group of stray dogs, yet he was a well-known and popular member of the community. He was accused of witchcraft by Emma Smith and beaten and thrown into the river. He later died of his injuries in the workhouse in Halstead.

Sharing what we have learnt

Applying our research to help others

Developing a lasting long-term ‘legacy’ of our community project was always part of our core aims of this project. We set out to learn about the stories of those accused of witchcraft in Essex and then to inspire others to learn more about their local heritage through sharing what we have learnt.

In this project we have:

1. Created opportunities for members of our community to learn more about what why people were accused of witchcraft locally in Essex, the stories of those accused and how they were treated.

2. Encouraged people to become Historians, learning more about their local heritage.

3. Worked with the Essex Records Office introducing our participants to the Archives, helping them to access them and how to use them to learn more about the overall treatment of those accused of witchcraft, the motives to why they were accused and the impact of the witchcraft trials.

4. Worked with local Historians including Professor Marion Gibson and the Essex Witches Museum to bring to research local stories of real people affected. We used Professor Gibson’s book “The Witches of St Osyth” as a starting point before reaching other local stories in Essex.

5. Developed a free education / learning resource pack for our community to use. A copy has been donated to the Essex Records Office.

6. Created a set of dramatic audio clips accompanying our learning pack to help make our resources more accessible to all.

These are available as visual ‘film’ formats on YouTube and as audio pieces on our website and have been donated to the Essex Sound Archives at the Essex Records Office for long-term preservation.

7. Created a set of ‘non-fiction’ audio clips and films accompanying our learning pack to help make our resources more accessible to all.

These can be accessed for free via our website and have been donated to the Essex Sound Archives at the Essex Records Office for long-term preservation.

8. Created a pop-up exhibition of witchcraft information banners sharing what we have learnt. These have been donated to the newly formed Essex Witches Museum for long-term use.

Devising a theatrical performance

We then created a special performance entitled “Inside the Essex Witchcraft Trials” to share what we have learnt with the local community. The performance included a selection of rehearsed readings of shirt stories, short plays, monologues and factual information.

The presentations were a huge success with many people saying that they had learnt so much and gained a new sense of empathy and understanding for those accused.

Pictures taken from our

show cases

Watch the Inside the Essex Witchcraft Trials

You can watch a recording of our Inside the Essex Witchcraft Trials here for free.

FREE EDUCATIONAL / LEARNING RESOURCE PACK

As part of our project aims, we have put together a special learning resource pack sharing what we have learnt along with suggested activities for our local community including schools and students to use for FREE.

A copy of this pack has also been donated to the Essex Records Office with the hope of preserving the legacy of our project for the long-term. A copy of this pack can be downloaded for free here:

A copy of the "Inside the Essex Witchcraft Trials script can also be downloaded below. This is a free resource for the community with no performance rights attached.

During our research into the stories of those accused we also found a list of those accused created by the Essex Police Museum. This list can be downloaded here:

Watch our Documentary Audio film

You can listen/watch our audio documentary film sharing our research into the Essex witchcraft trials below:

Acknowledgements

Our project could not have gone ahead without the support of the following people:

-The Heritage Lottery Fund

-The Essex Records Office

-Professor Marion Gibson

-The Essex Witches Museum

- Victoria West

-Kate O’Neill

-The staff at The Hythe Community Centre

-The staff at the Oak Tree Community Centre / St Annes Hall

-The Kelvedon Institute

- Andrew Forsyth

-Madeliene Ockendon

-Barry Ockendon

- Danni Minnican

-Kitty Whitley

- Charlie Whytock

- Pauline Warren

-Gill Adams

-Elsa Annushka Nigro

-Philip Antony

-CK Norman

- Ed Willcox

- Ian Russell

-Keith Norman

- James Cartmell

-University of Essex

-Kelvedon Players

This project and free learning pack was put together to offer a free resource pack to support others. We own no rights to the archive images used or external articles used in our research. No profits were made at any time.

This project was kindly supported by:

Under agreement with The Heritage Lottery Fund it is intended that all digital content featured in this project has been made under the guidance of the CC by 4.0 licensing