The London Pride Community Heritage Project

The London Pride community heritage project was a six-month project bringing members of the local community together to learn about and bring to life the story of the first London Pride in 1972. We worked with the National Archives and visited the Bishopsgate Institute to learn how to research as Historians, access and use artefacts and archives before devising a short theatrical performance and free education resource to share with the community. The project was supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund.

And the Project starts…

Engaging with the Community:

Right from the outset it was important for us to capture the attention of local people and encourage them to get involved and learn about the past. In preparation for the project, we used several tried and tested strategies as part of our public engagement strategy. These included:

-Posters and leaflets

-Social media (Our Instagram, Twitter and Facebook pages

-Library displays

-Invites to past members of our heritage projects

-Meet and greet sessions at local community groups

-Posters displayed at local Universities and LSE Library

-Word of mouth

And many more…

We were blown away by the number of people wanting to take part. We saw our BIGGEST intake of participants so far for our heritage projects

Visiting the National Archives and the Bishopsgate Institute

During the early stages of our project, we visited the National Archives where we worked with Victoria Iglikowski-Broad and Giorgia Tolfo. Our visit began with a tour around the archives before we were introduced to the archives, how they work and how we can access the archives to learn about the past. We were given a wonderful introduction to the background of the story so far of LGBTQ+ rights, giving us a clear understanding of where we have come from and some of the reasons why Pride came about. Although the National Archives hold more general facts and information regarding laws and legal matters and society as a whole, it gave us an invaluable starting point. We were then shown some of the artefacts held at the Archives including books, letters, newspaper articles, photographs and we were able to explore these in depth. The visit enabled us to formulate our key historical questions which we wanted to further investigate.

We then reinforced this with our visit to the Bishopsgate Institute where we were given more independent research time, putting into practice the skills we’d learnt at the National Archives to further investigate our focused questions. We split into groups each taking on different areas such as the different kinds of placards and banners used in the first Pride, the history of Drag artists and their role in the history of Pride, exploring key figures such as Louis Eakes and the impact which he had in the coming of the first Pride. The Bishopsgate staff were amazing and extremely helpful in guiding us to specific books, newspaper articles, galleries. Some of our participants returned several times after to continue with their research.

Read our Blog about our visit to the National Archives here

Read our Blog about our visit to the Bishopsgate Institute here

Setting the scene:

The history of Gay rights in the UK

Pride is a global movement

fighting for equal rights for

LGBT people all over the world.

LGBT stands for lesbian, gay,

bisexual and transgender.

Sometimes a Q+ is added which

stands for queer and + is an

inclusive symbol to mean 'and

others' to include people of all

identities. As well as an

opportunity to raise awareness of the fight for equal rights for the LGBT community, Pride is also a celebration of diversity.

Brief historical overview

Until recent decades, people who challenged sexual or gender norms were seen as a ‘threat’ to the

‘Natural order’ of society. It has never been illegal, as such, to be gay, but the associated sex acts

between men have been punishable at various times throughout history. Changing the gender

you presented as has not been regarded a criminal act, but the law and society could make it very

difficult.

In our first workshop we researched and explored the ‘history of Gay rights’ developing an understanding of the journey which our LGBTQ+ community have gone from Medieval times to the current day. We outlined who some of the influential people were and key important landmarks in time which helped shape our LGBTQ+ history. We then created a short summary article for our free learning resource.

Decriminalisation

The 1967 Sexual Offences Act finally acted on Wolfenden’s recommendations a decade later and decriminalised sex acts between men. However, it did not grant homosexual men a parity with heterosexual couples. There was a higher age of consent, the Armed Forces and Merchant Navy was exempted, and acts were only decriminalised ‘in private’. Arrests actually increased – the police and public were more aware of the parameters of the law. It only applied in England and Wales. Equivalent law changes did not happen in Scotland until 1980, and Northern Ireland until 1982. But, while only partial, the 1967 Act was a huge step forward and galvanised LGBTQ+

campaigns for greater equality. The 1970s saw a shift in political consciousness towards pride and equal rights; in the UK it was the decade of the first Gay Pride parade, the opening of Gay’s

the Word bookshop, and the launch of Switchboard, one of the first LGBTQ+ helplines. Campaign groups such as the Campaign for Homosexual Equality and the Gay Liberation Front were increasingly active.

You can download our article “Setting the scene: The history of Gay rights in the UK” here

Alternatively, you can listen to an audio version here:

The History of Gay Rights in the UK:

We've also made a short film about the History of Gay rights in the UK below:

The Stonewall Riots: the riots that changed gay rights history

The Stonewall riots were a series of spontaneous riots and demonstrations against a police raid that took place in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, at the Stonewall Inn, in the Greenwich Village neighbourhood of Lower Manhattan in New York City. Although the demonstrations were not the first time American LGBTQ people fought back against government-sponsored persecution of sexual minorities, the Stonewall riots marked a new beginning for the gay rights movement in the United States and around the world.

Very few establishments welcomed openly gay people in the 1950s and 1960s. Those that did were often bars, although bar owners and managers were rarely gay. The Stonewall Inn was owned by the Mafia and catered to an assortment of patrons. It was popular among the poorest and most marginalized people in the gay community: drag queens, representatives of a newly self-aware transgender community, effeminate young men, hustlers, and homeless youth.

Police raids on gay bars were routine in the 1960s, but in contrast to what was typical for raids at the time, the Mafia was not alerted by police prior to their arrival, nor was the NYPD's sixth precinct. Beyond this, raids typically occurred on weeknights in the early evening, when bar crowds were expected to be small. The Stonewall raid, in contrast, was to take place late on a Friday night, when crowd sizes were expected to be at their highest. Officers quickly lost control of the situation at the Stonewall Inn and attracted a crowd that was incited to riot. Tensions between New York City police and gay residents of Greenwich Village erupted into more protests the next evening and again several nights later. Within weeks, Village residents quickly organized into activist groups to concentrate efforts on establishing places for gays and lesbians to be open about their sexual orientation without fear of being arrested.

Following the Stonewall riots, sexual minorities in New York City faced gender, class, and generational obstacles to becoming a cohesive community. Over the following weeks and months, they initiated politically active social organisations and launched publications that spoke openly about rights for gay and trans people. The first anniversary of the riots was marked by peaceful demonstrations in several American cities that have since grown to become pride parades. The Stonewall National Monument was established at the site in 2016.

You can download a Free information sheet which we created about the "Stonewall Riots" here:

Alternatively, you can listen to an audio version here:

The Stonewall Riots:

We've also made a short film about the Stonewall Riots below:

Attitudes towards the LGBTQ+ community in the 1960s & 70s

In 1958 the Homosexual Law Reform Society (HLRS) was founded to campaign for the implementation of the reforms in the Wolfenden Report. The Albany Trust was set up to campaign against homosexuality being categorized as a mental health disorder and the terrible treatment of LGBTQ+ people in psychiatric treatments, like conversion therapy. These organisations, along with the Northwestern Law Reform Committee from 1964, lobbied for a change in the law.

The Sexual Offences Act in England and Wales in 1967 decriminalised sexual acts between consenting men over the age of 21, if the acts were carried out in private. The 1967 Act was only a ‘partial decriminalisation’. In fact, there was increased police intimidation of gay men after 1967. In addition, the age of consent for heterosexual couples to have consensual sex was 16. The law was far from equal. Men making their sexuality visible and being affectionate in public – for example kissing each other – could still be arrested for causing a breach of the peace or ‘gross indecency’.

For people who were Gay, Lesbian or Transgender, life was still very difficult despite the decriminalisation. Society had viewed homosexuality as a criminal or as many religions would state “a sinful” act should be punished and those who were Gay should be treated as an outcast. For many people they have no understanding or experiences of being around a gay person and don’t realise that a Gay person is just the same as a straight person except for one small thing. Society was heavily influenced by external factors such as old-fashioned views, media, religion, education, fear and a lack of understanding. Because of this, members of the LGBTQ+ community were subject to:

-All forms of bullying

-Hate crime including abuse e.g. spat at, beaten, personal property vandalised

-Name calling

-Loss of jobs

-Loss of housing

-Victimization from the police – often being arrested for other offences such as gross indecency, importuning.

-Labelled as perverts and child predators

-Outed and shamed in public

-Refused service in cafes, bars, transport etc

-Alienated by families, friends and churches

-Made to feel guilty, ashamed.

Many Gay people felt that it was still safer to live their lives in secret and were scared to ‘come out’ or be who they were. Others were constantly victimised at work, in public and alienated by society. It was still very dangerous being out and proud.

You can listen to an audio version here:

As part of our research application work, we used our research from the National Archives and Bishopsgate Institute to explore the attitudes towards members of the LGBTQ+ community during the 1960s and 70s. We also found that watching the BBC Archives, including the press conference with Sir John Wolfenden about his published report on Homosexuality, The Man Alive documentaries, This time of day and Male Homosexuality. (A series of interviews with homosexual men in 1965) We also used research donated to us by Peter Tatchell who was one of the founding members of the first London Pride march.

During our workshop we used group work, discussions and performance techniques to explore societies attitudes towards the LGBTQ+ community at the time. We quickly realised that these attitudes were heavily influenced by external beliefs and opinions. Even when after the decriminalisation act, homosexuals were still heavily targeted and discriminated against. We used role-play, improvisations, discussions and group work to create a clear understanding of how it felt to be Gay at the time and why society felt they way it did.

Focused workshop: How did the Gay community feel during the 1960s/70s?

LOST | UNSAFE | OUTCAST | CONFUSED | BULLIED | GUILTY | ASHAMED |

LIVING A DOUBLE LIFE | RESENTFUL | TRAPPED | ISOLATED | UNWORTHY |

PARANOID | HOPEFUL | REBELLIOUS | ALONE | UNLOVED | WORRIED |

IN NEED OF PROTECTION | SINFUL | MISUNDERSTOOD | VICTIMISED |

Applying what we'd learnt learnt

As part of our project, we researched into people’s stories from exploring the Bishopsgate Institute, National Archives, the media such as BBC documentaries and speaking to people about their personal experiences. Two stories in particular stood out to us which inspired us when creating our characters for our Proud play. Both the characters “Graham” and “Liz” were inspired by two interviews which we found on the “Man Alive” BBC documentary series recorded at the time. Both pieces explored the attitudes towards Gay people in the 1960s giving us a first-hand insight into what it was like to be Gay at the time and what motivated the London Pride to begin. It also taught us that it wasn’t just those who were Gay who were affected. It opened our eyes up to the wider picture. Particularly, in the Liz scene which sees a widower reflecting upon marriage to a Gay man. It encouraged us to create a play which shows not just a group of characters who are Gay, but the people around them such as Liz, Billy’s brother and father.

Graham

A transcript can be downloaded here:

Liz: (A widowers tale)

You can download the transcript from the interview here:

Rose Robertson

A former spy, she set up one of the first gay and lesbian helplines

In 1965, Rose took in

two young male

lodgers who she

quickly realised were

lovers. Hearing that

they had suffered because of their parent’s homophobic attitudes, Rose was eventually prompted to set up Parents Enquiry, Britain’s first helpline to advise and support parents and their lesbian, gay and bisexual children, which she ran from her Catford home in south-east London for three decades.

Rose was soon flooded with over 100 phone calls and letters a week. These came from distressed gay teens, many of whom had self-harmed because of homophobic prejudice, and from parents who were variously bewildered, distraught, angry, guilty, ashamed and hostile towards their children’s homosexuality. Often, she mediated between parents and kids, nearly always successfully. As a middle-aged and thoroughly heterosexual housewife, she was a reassuring figure. Occasionally, she was verbally abused and physically attacked by irate mums and dads. Usually, she won them over in the end. She was also targeted by homophobes, with arson attacks on her home, excrement dumped on her doorstep and torrents of abusive phone calls and hate mail.

From the mid-70s onwards, a growing number of referrals came from the police and social services. Authorities who had been wary of supporting gay teenagers, some of whom remained classed as criminals until 2001, were impressed by her family-oriented approach to reconciling gay children with their parents.

Rose won public support from Marjorie Proops and Claire Rayner, the leading agony aunts of the era. She was a frequent speaker at universities, churches and medical seminars, and was a regular on TV and radio throughout the 1970s and 80s.

You can download our free information page about Rose here:

Alternatively, you can listen to our audio here:

The History of Drag in the UK

Despite the empathies of the Gay rights movement being very much placed on men during the 1960s and 70s, the role of Drag queens was still very important. Drag has been around since Shakespearean times. In fact, the word ‘drag’ is believed to have theatrical origins too. The dresses men wore to play female characters would drag along the floor. During our research, we developed an information sheet exploring the history of Drag which can be downloaded below. There have been several notable figures who helped to shape the evolution of Drag especially over the past 150 years. These include Princess Seraphina. Otherwise known as gentleman’s servant John Cooper, Dan Leno and George Lacy, Vesta Tilley, Danny La Rue, Dame Edna Everage, the flamboyant creation of comedian Barry Humphries and not forgetting the one and only Lily Savage created by the brilliant Paul O’Grady. Drag Queens have been at the forefront of political change often pushing forward opinions in demonstrations and challenging societies views. They’ve become the mother to all Gays across the world. Yet, Drag is also about personal identity and acceptance for you are. In fact, Drag could be described as being the heart of what it is to be part of the LGBTQ+ community.

You can download our free information page “The history of Drag in the UK” here:

The Torchlight Rally – 1970

More than fifty years ago, on a Friday evening, about 150 defiant members of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) gathered in Highbury Fields. They were seething, enraged and fed up with the treatment of gay people by the police. In this case, there had been an incident two days before involving a young man called Louis Eakes. Eakes had been arrested for importuning on Highbury Fields which was a popular cruising spot at the time. In contrast to the act of “cottaging” – procuring sex in a public toilet – importuning was a crime a person could be easily charged with. A man who smiled, winked or was just flirtatious with another man could be booked for importuning. Eakes was caught in a sting operation by the police. Although, Eakes maintained he was merely looking for a light for his cigarette. He was arrested. When word made it to the GLF, the lack of evidence, combined with the sheer volume and frequency of arrests compelled the group to mobilise and to act.

The 150 GLF members at this organised demonstration, the first of its kind in Britain, carried candles and torches, held hands and kissed in protest as the police watched the procession take place. The seeds of what we now call Pride began as an act of protest, and while rights have expanded for LGBTQ+ people in Britain, the celebrations we have now must remain an act of defiance.

You can read more about the Torchlight rally by downloading our free information sheet

Alternatively, you can listen to our audio here:

Sylvie

For Paul O’Grady

SYLVIE: Oh, sweetie darling, I’m sorry to disappoint you, but there was no amateur dramatics in my coming out story. Lady Delores Jones! She was doing Betty Davies as Joan of Arc in a seedy basement somewhere in Regents Park. My mother worked behind the bar to make ends meet. She used to make a bed for me on one of the shelves under the counter, but I'd sneak up just to watch Delores. Those were the days. She was divine.

The blunt force of the baton couldn't stop the show. It was the same when I was old enough to take to the stage myself. Nothing could stop us. We felt that we could fly. It was real love. We were children of the night and every one of our hearts burned brightly. And we a family and we had each other’s backs. Sure, it was tough, and we had to learn to be tough. (Chokes back the tears) Bothwell Browne, Reg Stone, Hal Jones, Danny La Rue... they've all felt it...and my very own Benny. Oh, I was beautiful back then. None of these wrinkles and bags. Every Friday we'd emerge reborn and boy, we'd dance till dawn. Making history and breaking laws. We were heroes in fancy wigs and long heels! (Short laugh) Boy, did we look good. And we were proud.

Watch the Torchlight rally here:

You can watch a clip from our performance of the Torchlight rally here:

The Gay Liberation Front (GLF)

There were several groups that fought for the liberation of LGBTQ+ people in Britain in the 1970s. The Campaign for Homosexual Equality (CHE), founded in 1969, is the longest-running group campaigning for LGBTQ+ rights in the UK. Others, such as the UK branch of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), were founded in the aftermath of the Stonewall uprising.

“GAY IS GOOD! ALL

POWER TO THE

OPPRESSED PEOPLE”

The British branch of

the GLF was set up in

1970 at London School

of Economics by Bob

Mellors, a student there,

and Aubrey Walter.

They met at the Black

Panthers’ Revolutionary Convention held the previous summer in the US. “GAY IS GOOD!” were the words that signed off the British GLF’s initial list of demands. “ALL POWER TO THE OPPRESSED PEOPLE”.

The GLF set up meetings and workshops that brought people together to discuss key issues around LGBTQ+ oppression and activism. This time is sometimes referred to as the ‘pride before pride’. It organised activities such as dances and ‘gay days’, gatherings held in London parks like Victoria Park and Finsbury Park that also featured games, sing-a-longs and picnics.

There were also ‘kiss-ins’, where people publicly kissed each other as a form of protest. This was a bold act. Some “homosexual acts” had been made legal in the passing of the Sexual Offences Act in 1967 – but only those done in strict privacy between adults over the age of 21. Police arrested those they saw as same-sex kissing in public for ‘breaching the peace’ or ‘gross indecency’.

The GLF also organised some of the country’s first direct action events and protests.

You can download our free information sheet here:

Alternatively, you can listen to our audio here:

GLF Demands:

-That all discrimination against gay people, male and female, by the law, by employers and by society at large, should end.

- That all people who feel attracted to a member of their own sex be taught that such feelings are perfectly normal.

-That sex education in schools stop being exclusively heterosexual.

-That the age of consent for gay people be reduced to the same as for straights.

-That gay people be free to hold hands and kiss in public, as are heterosexuals.

“Come together” GLF Newspaper

The newspaper of the Gay Liberation Front, Come Together, was formed by the GLF’s Media Workshop in 1970. From its earliest beginnings the magazine reflected the key concerns of the LGBTQ+ community of the time. One of its first issues covered the demonstration organised by the GLF in response to the treatment of the Young Liberal politician Louis Eaks, arrested for gross indecency for the ‘crime’ of approaching men on Highbury Fields to ask for a light.

You can find lots of issues of the “Come together” newspaper in the archives at the Bishopsgate Institute or by visiting their website by clicking the button below.

You can download our free information page here:

Alternatively, you can listen to our audio here:

Pride placards and banners

The Pride marches weren’t just about celebrating diversity, but they were also about making statements both politically and socially. It’s important to remember that the LGBTQ+ community were angry in 1972. It wasn’t about creating a rainbow celebration. People wanted change. People wanted to feel proud of who and what they were. They wanted acceptance.

Whist researching, we wanted to find some great examples of the language and slogans used on their banners and placards to get the message across. We used both the internet, books and our focused research at the Bishopsgate Institute to find examples:

I'm a paragraph. Click here to add your own text and edit me. It's easy.

The Gay Liberation Front Film:

We've also made a short film about the GLF below:

Transgender history in the UK

The history of transgender people in the UK has evolved over time, with varying recognition and cultural gender indicators. Transgender individuals were historically recognized by different titles and expressions of gender, such as dress.

Although trans* people have been found in all the societies we learn about as children, they are often ignored by schools, textbooks and historians. The reasons for this are complex and multiple. One issue is that trans* people are seen in a negative light in our current culture. This means it is not seen as valuable for us to learn their history. Another issue is that LGB identities and trans* identities have not been considered as distinct throughout history.

In our research, we put together a detailed timeline marking out the history of Transgender rights in the UK. You can download this as part of our free information sheet below.

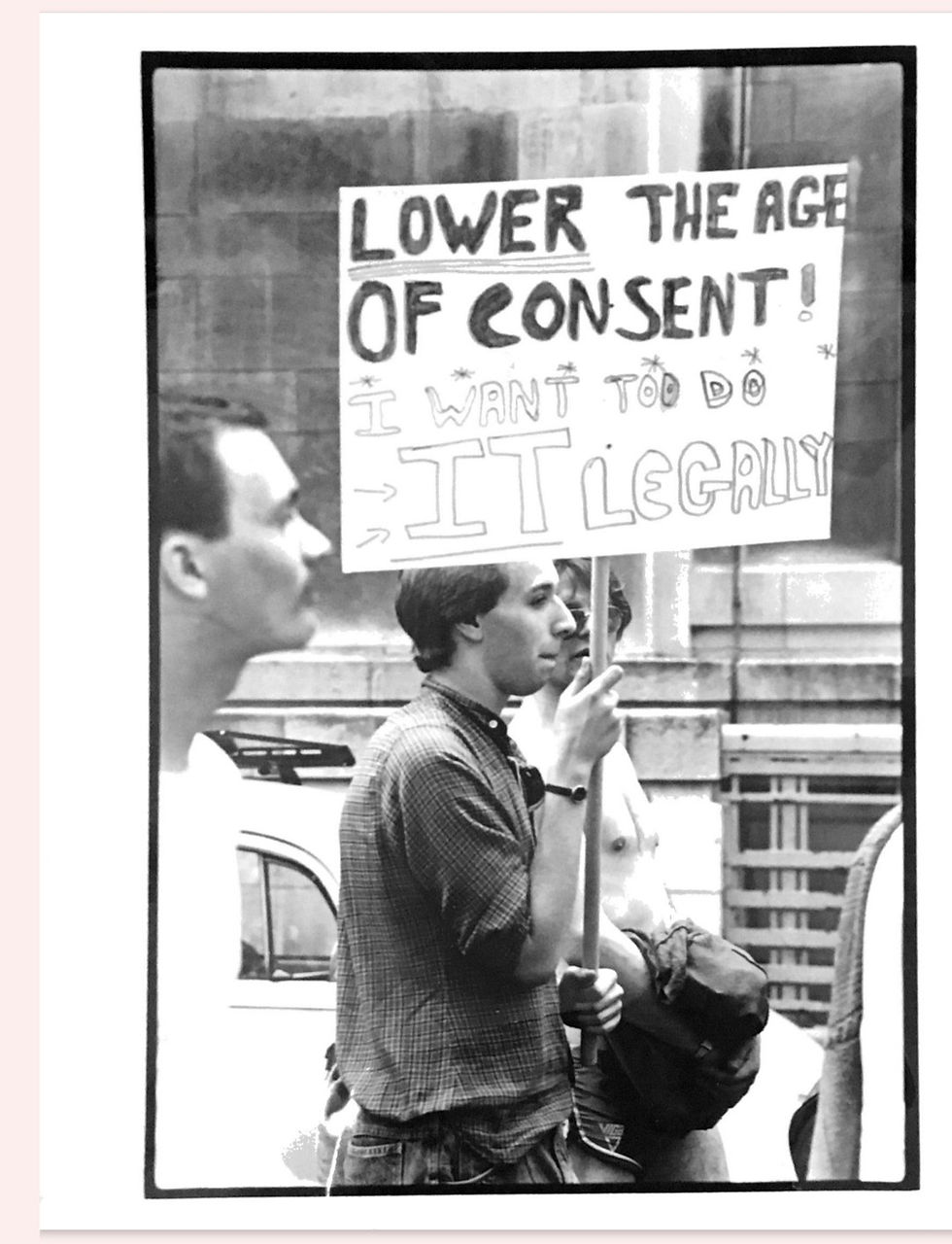

The Age of Consent March 1971

An ‘Age of Consent’ protest in

London was organised on

28 August 1971 by members

of the ‘under 21s’ group in the

Gay Liberation Front.

Restrictions on sexual activity

involving minors in the

United Kingdom and its

predecessors have existed

since medieval times. During

the 1970s, there was some political advocacy in favour of significantly reducing the age of consent. Meanwhile, over a similar time period, the unequal age of consent for straight and gay young people was campaigned against by the LGBT rights movement. More recently arguments have occasionally been made in favour of reducing the age of consent, generally to an earlier point in adolescence. The age of Consent demonstration was about the inequality in the age of consent for sexual acts between homosexual men and heterosexual couples. Both CHE and the GLF set up young peoples’ groups and campaigned on lowering the Age of Consent from 21 to 16 years for gay men, so it was the same as for heterosexual couples.

You can read more about the Age of Consent Demonstration in our free information page here:

Alternatively, you can listen to an audio version here:

How does Transgender history fit into the London Pride in 1972?

Pride was a protest for equality for all and although the term “LGBTQ+” was not known in 1972, we know that it wasn’t just Gay people who turned up to march. It was Gay, lesbian, Trans-gender…everyone. We felt strongly that this should be documented in our project and our learning resources. We chose to create the character of “Alex” in our Proud sharing to symbolise this and to inspire others to learn about the history of Trans-gender people and the struggles which they have...and still have today. We purposely created a monologue telling the story of Claude..., the woman with a painted beard to show the way which Transgender people were treated with the end conclusion that Alex who is telling the story, is fired from his role as a Solicitor for being Transgender. It’s a strong stink in the tail but serves as a reminder of the struggles which Transgender people face even today. Only recently, this year, Trans people have had their rights removed and are no longer protected under the Equality Act or legally recognised by the Gender Recognition Act. A decision which is backward thinking and alarmingly dangerous.

The Rose

In our research we came across a

wonderful article which spoke

about the rose being a symbol of

Transgender. We were so captivated by

this beautiful concept that we decided to feature this in our Proud sharing piece.

.png)

Watch Claude's monologue here:

You can watch a clip from our performance of the Alex's monologue about Claude here:

The first Gay Pride 1972

On 1 July 1972 a ‘carnival parade’ of protest was held from Hyde Park to Trafalgar Square London. It was the first Gay Pride in a city in the UK and the nearest Saturday to the Stonewall date of 28 June.

“We are gay, and we are proud, and we are going to enjoy ourselves.”

This statement was printed on the programme for Britain’s first Pride protest, which took place in London on 1 July 1972. A crowd of a few hundred travelled from Trafalgar Square to Hyde Park, setting the foundation for what’s now one of the biggest events of its kind worldwide. Numerous gay rights organisations took part, including the GLF and CHE, and 200 - 500 people turned up, but it was heavily policed. The march was part of a week-long demonstrations and ‘Gay Ins’ for London Pride. Many people who were Gay did not turn up in fear of being arrested or being bashed. That didn’t happen, but they were swamped by a heavy police presence. The march was a carnival-style parade, which went from Trafalgar Square to Hyde Park.

When the march arrived at Hyde Park, there was no festival or entertainment - just an impromptu DIY queer picnic, what was called a ‘Gay Day’. Everyone bought food, booze, dope and music. It was all shared around. They played camped-up versions of party games like spin the bottle and drop the hanky. It was more than good fun.

Whilst building a clearer picture of what it was like to be there during the first London Pride in 1972, we found lots of different people's recounts and memories which were invaluable in our research. You can read more about the First Gay Pride in our free information page as well some of the first hand memories of the people who were there.

Information Page

Memories of the First Pride by Peter Tatchell

Memories of the First Pride from Stuart Feather

Chant taken from the First London Pride in 1972

2-4-6-8.

Gay is just as good as straight.

3-5-7-9. Lesbians are mighty fine.

Give us a G.

G!

Give us an A.

A!

Give us a Y.

Y!

What’s that spell?

Gay!

What is gay?

Good?

What else is gay?

Angry!

A recount of the first Pride by Philip Rescorla

50 years on...an article about the London Pride veterans

The first London Pride 1972 Film:

We've also made a short film about the first London Pride 1972 below:

Download the lyrics to the chant here:

You can also listen to our information page here:

Why Pride is Still Needed and Its Importance to the LGBTQ+ Community

Looking back at how far Pride

has come since 1972, we’ve come a long way. Change is happening and progress is being made thanks to Human Rights Activists such as Peter Tatchell and support from people like Rose Robertson who formed the

Parents Enquiry helpline for parents of Lesbian and gay children in 1968. Although we no longer have many of the groups who laid the foundations of Gat rights movement such as the GLF, the baton has been securely past on, and work continues. We’ve made a lot of progress.

So why is Pride still important?

1. Visibility and Representation

2. Community and Solidarity

3. Advocacy and Awareness

However, in our evaluation discussion workshop, we raised the question of how Pride has changed over the years and has it almost become a victim of its own success. In recent years, Pride has been co-opted by corporations. The marches are now a business model, with corporate sponsorships and marketing taking precedence over the Pride’s original purpose. This commercialisation risks reducing Pride to a marketing opportunity and a corporate tick exercises in diversity and inclusion, rather than a meaningful movement for social change. As one of our participants quite rightly highlighted – it’s amazing how many companies, local councils suddenly dig out and start waving the pride flag from their rooftops during pride month as a business opportunity but yet it’s nowhere to be seen during the other eleven months of the year! As such, there is a growing call within the community to return Pride to its roots of protest and advocacy, focusing on the fundamental issues of equality and justice.

The Need to Return to Roots

Despite legal victories, the rights of LGBTQ+ individuals remain vulnerable. Legislative changes can be reversed, and social attitudes can regress. Therefore, Pride must return to its roots as a protest and a call to action, emphasising the ongoing fight for equality and justice. It is essential to maintain the spirit of resistance and advocacy that characterised the early Pride movement in 1972.

Conclusion:

There is still more that can be done. Hate crime towards members of the LGBTQ+ community is still a constant blackened stain on our society. There are also still 64 countries in the world which have laws that criminalise homosexuality. Pride is about acceptance, equality, celebrating the work of LGBTQ+ people, education in LGBTQ+ history and raising awareness of issues affecting the LGBTQ+ community. It also calls for people to remember how damaging homophobia was and still can be. Pride is all about being proud of who you are no matter who you love.

You can read a full summary of why Pride is still important here:

What have we achieved so far?

-

In 1994 - The age of consent for two male partners was lowered to 18.

-

In 2000 - The ban on gay and bisexual people serving in the armed forces is lifted.

-

In the same year, the age of consent is equalised for same- and opposite-sex partners at 16

-

2002 - Same-sex couples are given equal rights when it comes to adoption.

-

2003 - Gross indecency is removed as an offence.

-

2004 - A law allowing civil partnerships is passed

-

2007 - Discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is banned.

-

2010 - Gender reassignment is added as a protected characteristic in equality legislation

-

2014 - Gay marriage becomes legal in England, Wales and Scotland

Sharing what we have learnt

Applying our research to help others

Developing a lasting long-term ‘legacy’ of our community project was always part of our core aims of this project. We set out to learn about the first London Pride which took place in 1972 and then to inspire others through sharing what we have learnt.

In this project we have:

-

Created opportunities for members of our community to learn more about what life was like for members of the LGBTQ+ community during the build up to the first London Pride identifying the motives as to why the pride march was created and what they hoped to achieve.

-

Encouraged people to become Historians, learning more about their local heritage.

-

Worked with the National Archives introducing our participants to the Archives, helping them to access them and how to use them to learn more about the overall treatment of Gay people, the laws which governed them during the 1960s and 70s and how this fitted into the lead up to the First Pride march.

-

Worked with the Bishopsgate Institute visiting and using the local archives to research personal recounts and memories of the first pride, accessing newspaper articles, pictures, badges, placards and banners and social influences to help develop a clearer understanding of what it was like to be Gay during the period.

-

Developed a free education / learning resource pack for our community to use. These materials can be accessed for free on our website.

-

Created a set of audio clips accompanying our learning pack to help make our resources more accessible to all. Our

-

7. Re-created two scenes inspired by two BBC interviews from the Man Alive documentary series which we filmed especially for this learning pack.

-

8. Created several short films to support our learning resource pack including:

-

9. Devised a small theatrical performance called “Proud” inspired by what we have learnt bringing to life the story of the First London Pride which was performed at the Courtyard Theatre, London in June 2025 (Pride month)

Devising a theatrical performance

We created a special theatrical performance to share what we have learnt during our community heritage project. “PROUD” was performed at the Courtyard Theatre in June as part of London’s Pride month. As well as showcasing what we have learnt, we also explored the impact which fashion had upon the LGBTQ+ community and how music influenced the LGBTQ+ community. We discussed the importance of reclaiming words, phrases and slurs which have been used against us to empower, changing these negatives into positives. We have also developed information pages about these which can be found in our free learning pack.

PROUD was a huge success and we learnt so much from the project from being historians to leaning about our LGBTQ+ heritage.

![20250607_134120[1].jpg](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/187097_aa16e70e6760475281ec4907b7b4425f~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_341,h_182,al_c,q_80,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/20250607_134120%5B1%5D.jpg)

Pictures taken from our show cases

Watch the PROUD play

You can watch a recording of the PROUD performance here for free.

FREE EDUCATIONAL / LEARNING RESOURCE PACK

As part of our project aims, we have put together a special learning resource pack sharing what we have learnt along with suggested activities for our local community including schools and students to use for FREE.

A copy of this pack has also been donated to the Bishopsgate Institute and the National Archives with the hope of preserving the legacy of our project for the long-term. A copy of this pack can be downloaded for free here:

You can also download a special article "An archived-inspired theatre performance" written by Vicky Iglikowski-Broad from the National Archives celebrating our achievements and the wonderful collaboration between us and the National Archives

This project was kindly supported by:

Under agreement with The Heritage Lottery Fund it is intended that all digital content featured in this project has been made under the guidance of the CC by 4.0 licensing